R2K Submission on Critical Infrastructure Protection Bill

Right2Know Submission on the Critical Infrastructure Protection Bill

1 Introduction

The Critical Infrastructure Protection Bill (the Bill) seeks to replace the apartheid-era National Key Points Act, on the back of growing criticism of the Act and its questionable constitutionality. This Bill follows a promised review of the Act, initiated by former Police Minister Nathi Mthethwa in May 2013, and a draft version of the Bill published by the Civilian Secretariat for Police Service in 2016. R2K made comment on the draft Bill[1].

1.1 About the National Key Points Act

The National Key Points Act (“the Act”) is an apartheid security law passed in 1980 to deal with the perceived threat of sabotage to apartheid infrastructure. Despite its role in propping up the Apartheid security state, for which the liberation movement rightly criticised it, the Act remained intact during the transition to democracy and has now found a second life in the post-apartheid era, though its constitutionality is under question.

The stated purpose of the National Key Points Act is to identify buildings and locations whose functioning is considered vital to national security; the Minister of Police may declare any such site to be a National Key Point. Once this happens, the owners of the site are responsible for putting certain security measures in place (the level of security is tailored to the importance of the site). Under the Act it is a crime to reveal any information whatsoever about the security measures – the maximum penalty is three years in prison or a R10,000 fine.

Quite simply, the Act has privatised and outsourced the use of “national security” as a tool to promote secrecy and undermine freedom of expression and accountability in the public and private sector. Its broad, vague and draconian powers have led to numerous abuses grand and small – and indeed, its vagueness and lack of oversight mechanisms have allowed officials to exercise powers of secrecy and repression that go far beyond the actual provisions of the Act.

These have included countless anti-democratic maneuvers by officials in government and the private sector using the National Key Points Act as a shield from criticism, either by denying access to crucial information held by National Key Points (especially in the case of corporate polluters) or by hindering protests. Although the Act does not expressly prohibit gatherings at National Key Points, in many cases the authorities and private entities have framed certain protests as being a direct threat to a National Key Point’s security. Members of the South African Police Service (SAPS) claim to have a policy prohibiting protests within 100m of National Key Points; R2K has never seen such a policy and consider any such policy unlawful.

The fact that the very list of sites protected by the Act was a closely guarded secret has been a particular point of controversy, and eventually a matter settled by the courts. In Right2Know Campaign and Another v Minister of Police and Another, the South Gauteng High Court ordered the Ministry of Police to release the list of National Key Points to the public.

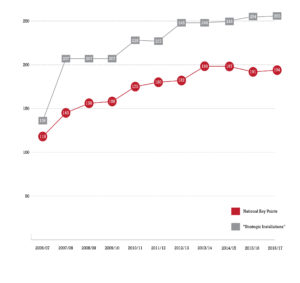

It is a significant concern that the number of National Key Points and Strategic Installations has increased considerably in the years under record. SAPS annual reports show that between 2007 and 2017, the number of National Key Points grew by 66% and the number of sites designated as Strategic Installations grew by 87.5%.

The apparent rapid expansion of these policies represent a troubling shift towards greater securitisation, in which ‘national security’ priorities and structures play an increasingly powerful and visible role in our politics and public life.

1.2 R2K’s position on the Critical Infrastructure Protection Bill

The Right2Know has consistently called for the scrapping of the National Key Points Act, and Right2Know structures have documented, exposed and challenged abuses of the Act on the ground. The apartheid-era Act must be scrapped in its entirety, not tinkered with, and any new law must be rooted in openness and transparency, as narrowly defined as possible, with strong, independent oversight – both through formal institutions and through the provision of full public participation and citizen oversight. Above all, activities in the public interest, including whistleblowing, journalism, protest and dissent should be protected from prosecution.

The Right2Know Campaign acknowledges that there are genuine safety and security needs at certain key infrastructure, but in light of the significant risks of abuse of power, has developed a ‘7-Point Freedom Test’ to determine whether any such policy is guided by the values above:

- Will there be transparency about which public and private bodies are protected by this Bill?

Yes: The Bill requires disclosure of Critical Infrastructure, but greater transparency is needed.

- Are there protections to ensure that any secrecy powers are strictly limited to legitimate national security matters and no more?

No: Through its broad scope and wide-ranging offences, the Bill’s secrecy measures are expansive.

- Does the Bill protect the right of whistleblowers, journalists and activists to expose secrets in the public interest?

No: The Bill replicates the weaknesses of the Secrecy Bill and fails to protect people who expose secret information in the public interest.

- Will we be able to take photographs and video of these places?

No: The Bill would create unjustifiable conditions in which recording, photographing, and taking videos at Critical Infrastructure would be prohibited.

- Are there protections to ensure this Bill promotes the right to protest against public and private bodies?

No: The Bill contains harsh new offences and penalties that could criminalise and intimidate protesters and striking workers.

- Is the scope of this Bill narrowly defined to ensure that it does not contribute to the spread of securocratic policies?

No: The Bill may actually expand the scope of the existing Act signficantly.

- Are there clear checks and balances to ensure that anybody who is given powers under this Bill can be held publicly accountable?

Maybe: The Bill strengthens the oversight role of Parliament and creates a more transparent Council to monitor the implementation of the Bill. But the Council’s oversight powers are weak. There is little provision to hold accountable the owners of Critical Infrastructure.

In summary, the Critical Infrastructure Protection Bill does not meet these principles. The Bill is likely unconstitutional owing to its overly broad scope, lack of transparent approach despite making substantial incursions into various fundamental rights. The Right2Know Campaign therefore rejects the Bill in its current form.

2 Scope of the Bill

The question of the Bill’s narrowness of application is critical in determining whether the Bill would be open to abuse if passed into law – meaning that we must look closer at the criteria for determining which sites can be declared ‘Critical Infrastructure’ and how it attempts to transfer National Key Point-like powers to these institutions.

The considerations include:

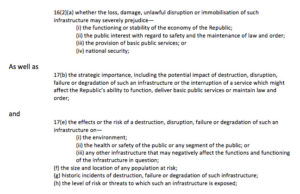

Section 16(2) spells out the very wide and vague grounds in which the Minister of Police may declare any site to be ‘Critical Infrastructure’. These include whether damage or disruption to the site would “prejudice” national security, which is not defined in the Bill, but which is unacceptably broadly defined in related legislation such as the Protection of Information Act of 1982 or the Protection of State Information Bill which has yet to be signed into law).

But the Bill actually goes beyond the 1980 Act’s understanding of what sites would require such protection, with the inclusion of new factors which fall outside of traditional ‘national security’ considerations must now also be taken into account, such as ‘provision of basic services’, ‘functioning of the economy’, ‘the public interest with regard to safety and the maintenance of law and order’, and very many open-ended considerations per section 17.

Read in total, the criteria for critical infrastructure could well include any and all government buildings, including police stations, clinics and municipal buildings; university campuses and schools; very many private sector entities including financial institutions and centres of commerce; mines, refineries and industrial sites. It is impossible to project how many new entities could be classifiable as Critical Infrastructure in these terms, but it is certain to be many more than the roughly 200 sites protected by the National Key Points Act – indeed, it may run into the thousands or even tens of thousands. These broad definitions may be drafted with the best intentions, but in a national security law they are a recipe for abuse.

Other problems relating to the Bill’s scope include:

- The Bill’s specific definition of “Basic public services” is overly broad and open ended, creating opportunities for unduly curtailing the rights to protest action and strikes. It is worth noting that a sizeable proportion of the South African population is already not receiving these services through service delivery backlogs, corruption, inappropriate macroeconomic policies and not as a result of the disruption of any national key point or critical infrastructure.

- While the Bill does attempt to assign “Risk categories” to critical infrastructure, namely “high”, “medium” and “low”, but none of these has been defined in the Bill despite the implications that these may have for shaping security measures.

- The Bill’s definitions for ‘security’ and ‘security measures’ are open-ended. Any such provision must be narrowly defined to avoid the risk that owners or controllers of Critical Infrastructure may seek to expand their powers beyond vital security-related issues.

- The Bill hands significant powers to private persons and entities in control of Critical Infrastructure. While Section 24 imposes obligations on owners, Section 25 confers extensive discretion on a private person/entity to take whatever lawful steps they “may” consider necessary. There is already experience under the National Key Points Act of the potential for abuse this creates.

3 General transparency measures

The Bill attempts to depart from the unjustifiable secrecy surrounding implementation of the National Key Points Act, most notably in the list of sites protected by the Act. However, these measures do not go far enough.

3.1 Declaration of Critical Infrastructure

The Bill’s stipulation that sites registered or de-registered as Critical Infrastructure will be announced by government gazette. This is a logical outcome of the findings of the High Court in Right2Know Campaign and Another v Minister of Police and Another.

However, the principle of proactive and regular transparency stipulates a public and regularly maintained register of protected sites should be available over the internet and included in reports to Parliament. These should prominently note which sites were registered and de-registered and when.

3.2 Reporting to Parliament

The Bill would require the Minister of Police to make annual reports to Parliament. While strengthening Parliament’s oversight role is to be welcomed, this provision does not clarify to whether this reporting will happen to the National Assembly or to a Committee in Parliament. In previous policy discussions during the Ministry’s revision process on the National Key Points Act, it has been intimated that reporting to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence. Given the Intelligence Committee’s poor track record on transparency, which includes withholding non-sensitive information and protracted delays in releasing reports, R2K calls for a more detailed reporting function which requires that the Minister’s reporting function is to the Police Committee, and that this report is tabled publically.

3.2 Lack of public consultation on declaration of Critical Infrastructure

It is problematic that neither the Minister nor the Council is required to engage in public consultation on a decision to declare a specific entity as “critical infrastructure” Section 18(3)(a)(ii) requires the National Commissioner to call for public comments, when an application for a declaration is initiated by the “person in control”, without stipulating any further requirements to ensure that consultation is meaningful or that adequate time is provided. Inexplicably there is no provision for public consultation under section 19, where the application is initiated by the National Commissioner.

Similarly sections 22 and 23 should also entail requirements for public comment. Council “guideline” should also be subject to consultation. It should also be noted that for many different types of entities capable of being declared Critical Infrastructure, this declaration may seriously affect disempowered or marginalised communities. Such instances show that public consultation provisions need to go beyond mere announcement by gazette but call for a more extensive consultative process.

4 Offences

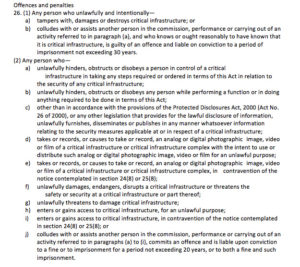

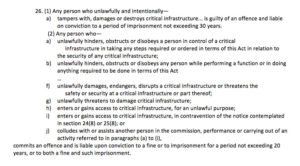

Section 26 of the Bill provides for the offences and penalties in relation to Critical Infrastructure. This provision of the Bill offers the deepest problems yet, and are worth replicating here in full.

These offenses potentially criminalise legitimate disclosures of information and acts of protest and dissent in a variety of ways. They offer many of the same problems as the offences contained in section 10(2) of the 1980 National Key Points Act – and some new ones.

4.1 Criminalising freedom of expression and access to information

R2K’s position is that no law may gag the release of information that should be in the public interest, and that the law should robustly protect the rights of journalists, academics, activists and whistleblowers who seek out such information and bring it to the public. Sections 26(2)c-e contain egregious secrecy clauses which ride roughshod over that principle.

4.1.1 Secrecy about security measures

Section 26(2)c effectively places an almost total veil of secrecy on any information related to the safety and security measures of ‘Critical Infrastructure’, with a few fig-leaf exemptions (if such disclosure is regulated through another law).

Firstly, this creates a far-reaching ‘gag order’ on many security measures that are not sensitive and are even visible to the passerby: a fence around the Engen refinery in South Durban, a security camera in the parking lot of a SABC station, a turnstile at Parliament, and very many other publicly viewable features of very many public institutions. To disclose their very existence, when they are actually not secret, nor sensitive, could be a criminal offence under this Bill.

Secondly, there are clearly instances where it is in the public interest for information about security measures at ‘Critical Infrastructure’ to be made public, including sensitive information. The most notable example is the disclosure by investigative journalists of security features and other upgrades at the President’s private homestead at Nkandla, which were vital to exposing possible waste of public funds and abuse of power. Another notable example would be investigative reports on changing security measures and standards of openness in Parliament between 2014 and 2016, which captured the public imagination in the aftermath of the ‘signal jamming’ incident at State of the Nation 2015. No genuine demonstrable harm was done by these disclosures, and they served a vital role in informing the public, yet these acts would be criminalised under this Bill.

It is furthermore unclear how the blanket secrecy on all security measures in s26(2) gel with the provision of s20(6), which stipulates that for each Critical Infrastructure, “the Minister may… determine that the publication of information regarding the security measures which must be implemented at such critical infrastructure be restricted”.

The exemption in the s26(2) secrecy clause, that disclosing information about Critical Infrastructure security measures will not be an offence if it is done in terms of the Protected Disclosures Act (PDA) or any other law, offers little relief. The PDA only protects employees who disclose information about their workplace, and only then once they have jumped through a number of administrative ‘hoops’. The main other applicable law would presumably be the Promotion of Access to Information Act, which requires someone to formally apply for access to records held by an information holder, and mandates a response within 30 or 60 days. While it must be emphasised that the transparency powers in PAIA do trump any secrecy provision in any other law, the slow, and painstaking procedures for information access in terms of PAIA do not meet the need for a full public interest defence in any secrecy provision. It should also be noted that civil society experiences show that compliance with PAIA is so low that roughly two-thirds of requests for information are simply ignored[2].

These provisions also replicate another key problem from the Secrecy Bill — “reversing the onus”. Simply put, like section 43 of the Secrecy Bill which would make it a criminal offence to make secret information public unless protected by a few narrow exemptions, the section may exempt certain people from prosecution, but puts the onus on them to prove that their action was exempted. By placing the burden on the accused to prove their action should be exempt, this provision places an unjustifiable restriction on freedom of expression.

The Bill also lacks other possible safety mechanisms, such as a ‘harm test’ which would determine whether or not an offence had been committed by the demonstrable harm that is caused by an action, rather than an action itself which may cause no harm. Effectively the Bill cannot distinguish between security threats and legitimate acts of dissent, protest, advocacy, whistleblowing and journalism.

4.1.2 ‘Banning’ videos and photographs at Critical Infrastructure

The Bill takes the extraordinary step of prohibiting the photographing, filming or recording of any aspect of a Critical Infrastructure – not just the security measures – if it is with intent of using such recording for an “unlawful purpose” (section 26(2)d), or in contravention of a notice posted by the owners (section 26(2)e). These provisions are are actually much more far-reaching than the restrictive measures in the Apartheid-era Act. On many occasions, Right2Know members or supporters have been harassed by police or private security when taking videos in public places near or at National Key Points. It is a key way that the Act has been invoked to shield these institutions from public scrutiny – but such secrecy powers are not actually contained in the 1980 Act; they were a fantasy of officials on the ground.

Section 26(2)e would effectively empower the staff member in charge of security at a Critical Infrastructure site to ‘ban’ photos, videos or other recordings at that place simply by posting a notice stating such a ban. This poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

Section 26(2)d, on the other hand, prohibits the photographing, filming or other recording at Critical Infrastructure if it is with the intent to use for “an unlawful purpose”. This qualification is no relief, because it creates a provision that is either unenforceable or which will be enforced far too much. It places a burden on security officials at these sites to decide whether someone who is filming or recording may at a later stage use it for an unlawful purpose. In practical terms, it creates conditions i which security officials or law enforcement can shut down a recording at any time, thus drawing a veil of secrecy around any institution that would be protected by this Bill.

4.1.3 Minimum requirements

To avoid abusive and restrictive provisions, R2K recommends the following minimum measures to any security law:

- Intention: Where offences are spelled out, as per section 26(2), a person’s intention should be key to determining whether not they have committed an offence. In the current drafting, s26(2) offences require only that the act be undertaken ‘unlawfully’, not ‘unlawfully and intentionally’

- Public domain test: there should be no penalties handed out for information already in the public domain, or in public view.

- Harms test: there should be no penalties handed out where there is no harm to national security.

- Public interest defence: where the public interest in disclosure outweighs the harm contemplated, there should be no offence.

- Furthermore, any prohibitions on filming or recording should be rejected outright.

4.2 Criminalising protest and strikes

The Bill adds new categories of offences not contained in the 1980 National Key Points Act, that may well be used to create harsh new penalties against protest and labour strikes at sites that are declared Critical Infrastructure. These include:

This effectively places extraordinary harsh new prohibitions on the right to strike or protest at institutions which are protected by this Bill, which would include government entities and private companies. It goes without saying that sites that meet the Bill’s envisaged criteria for ‘Critical Infrastructure’ are often the target of legitimate public protest and criticism, as well as labour grievances.

Almost all effective forms of protest and strikes are disruptive by their nature – albeit it temporarily. Actions that are disruptive but non-violent are still a Constitutionally protected form of free speech. It would therefore be extraordinary to criminalise such action – especially with such heavy-handed sentences.

The offence of “endangering” or “threatening” ‘Critical Infrastructure’ are so especially vague that they surely invite officials to abuse the powers of the Act. Even if such abuses could be challenged in court, this is too high a cost. Practical experience has shown that the justice system is most often inaccessible due to cost and simply does not mete out fair treatment to the poor and marginalised. The correct remedy is not to propose legislation with broad and expansive powers that invites officials to abuse them.

It should also be noted that where there are genuine incidents of violence and property destruction at Critical Infrastructure, these are already criminal acts that are prosecuted under the common law crime of malicious damage to property. Additional, excessively harsh criminal penalties are unnecessary.

4.3 Harsh penalties

In all offences in the Bill, the penalties are outrageously high – significantly higher, in fact, than the 1980 National Key Points Act. R2K believes these offences are drastically out of kilter with the values of our Constitution and hard won democracy.

5 Additional Concerns

5.1 Bill does not account for 248 secrets sites declared to be Strategic Installations

As R2K has stated elsewhere, National Key Points are just one category of secret ‘security’ sites. Another category of sites exists called Strategic Installations – with 255 such sites across the country.

At R2K’s behest, the South African History Archive (SAHA) has submitted a PAIA request to the police for a list of these Strategic Installations. Police have refused to disclose this information, but correspondence between R2K and the SAPS suggests that most Strategic Installations are national and provincial government buildings. It is not clear whether these are ‘civilian’ sites or military sites or both.

‘Strategic Installations’ were a feature of the Police Ministry’s 2007 Bill to amend the National Key Points Act. Though the Bill was withdrawn, it would appear that SAPS has implemented aspects of the Bill without any law to underpin it. Any attempt to repeal or replace the National Key Points Act should be cognisant of the need to roll back this unregulated practice. Currently the Bill appears to leave the practice intact.

5.2 Bill overlaps significantly with the Cybercrimes & Cybersecurity Bill

There is significant overlap between the Critical Infrastructure provisions of this Bill and the Critical Information Infrastructure provisions of the Cybercrimes Bill. Each Bill has created separate categorisations and procedures to be dealt with by separate government entities (SAPS and the State Security Agency); however, there are very many instances where the two policies may apply to the same entity or even the same infrastructure. R2K has registered its serious concern with the powers that will be granted to the State Security Agency under the Cybercrimes Bill, but this overlap also creates the risk of great policy confusion, including both overlaps and gaps in oversight.

The current formulation, per this Bill, seems to be that responsibilities and authority will be determined on a case-by-case basis. Simply put, these issues need to be dealt with in a single Bill.

6 Conclusion

Despite our fervent opposition to the National Key Points Act and longstanding demand to see it scrapped, Right2Know believes that this Bill does not represent a constitutionally sound replacement to that Act. It fails to substantially deal with some of the fundamental problems and unconstitutional provisions of the Act, as previously noted.

In its current form the Bill represents a continuation, not a departure, of the security-statist thinking that drove opposition to the National Key Points Act. It is a matter of deep concern that, far from being closely monitored and regulated at the margins of our society, security laws and security politics play an increasingly prominent role in South Africa’s public life, often at the expense of South Africa’s people.

While acknowledging several notable improvements and concessions in the current drafting, the Bill does not meet the 7-Point Freedom Test by which R2K believes such policies should be measured, and calls on the Committee to reject any critical infrastructure Bill that does not meet this test. The Right2Know Campaign thank the Committee for its work and would welcome any further engagement on this submission.

– Ends.

For further information on this submission, please contact murray@r2k.org.za

[1] R2K Submission, 20 June 2016. Available online: https://theright2know.org/2016/06/20/download-r2ks-submission-on-draft-critical-infrastructure-protection-bill/

[2] See Access to Information Shadow Report, 2017: https://theright2know.org/2017/09/28/shadow-report/