Defending the Right to Protest: comments on White Paper on Policing

Picket against police bruality, Delft police station, on Human Rights Day 2015.

R2K has made a submission on the draft White Paper on Policing, with a focus on protecting the right to protest and freedom of assembly.

Protest is a fundamental right used by communities across South Africa to exercise freedom of expression and highlight issues of social justice.

In the past ten years, police brutality against protesters has increased sharply, seemingly outstripping any increase in the actual number of protests – fuelling concerns that freedom of assembly is under threat.

R2K’s comments on the draft White Paper on Policing try to address the drift towards increasingly violent methods of policing when it comes to protest.

Our submission made the following calls:

- Bring an end to police violence against protesters

- Strengthen legal protection for protesters

- Develop a path to genuine demilitarisation of policing

- Curtail intelligence-led methods in public-order policing

- Bring perpetrators of police brutality to justice

Confronting myths about protest in South Africa

Unfortunately statements by police and other government bodies, often echoed in the media and public discourse, paint a misleading picture of the true state of protest in South Africa, which fuels attitudes and policies which undermine freedom of assembly and expression.

Protest does appear to be on the rise in South Africa, but statistics show the majority of them are peaceful.

Over the past ten years, there has been a dramatic increase in the incidents of deaths, assault and attempted murder by police during protests. This increase seems to be far out of proportion to any increase in the number of protests.

The official oversight structures have failed to bring justice in these cases. Of 204 complaints investigated by IPID in relation to public-order policing between 2002-2011, only one resulted in a conviction.

In July 2014, Minister of Police Nathi Nhleko announced an intention to demilitarise public-order policing – but questions remain about whether this is geared to address the deeper roots of militarisation. It remains to be seen what effect this will have on the right to protest, especially as the Ministry has proposed to use more intelligence-led approaches to policing protests, which suggests greater use of surveillance.

Download the submission here or read it below. The submission draws from R2K National Summit resolutions and research by Professor Jane Duncan (as well as a concept paper on police brutality prepared by Duncan), and R2K’s 2014 Secret State of the Nation Report.

—————————————

Defending the Right to Protest: R2K comments on Draft White Paper on Policing

1. Introduction

The Right2Know Campaign (“R2K” and “The Campaign”) was launched on 31 August 2010 as a coalition of organisations and individuals responding to the initial Protection of State Information Bill in Parliament. However, since then it has expanded its mandate to become a broad-based, grassroots campaign to champion and defend information rights and promote the free flow of information in South Africa.

R2K’s vision is to:

“seek a country and a world where we all have the right to know – that is to be free to access and to share information. This right is fundamental to any democracy that is open, accountable, participatory and responsive; able to deliver the social, economic and environmental justice we need. On this foundation a society and an international community can be built in which we all live free from want, in equality and in dignity.”

The activities of the Right2Know Campaign are undertaken through provincial working groups in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape, and coordinated nationally through an elected national working group. These structures are made up of members of local civic organisations from many communities and grassroots struggles, as well as individual activists from a range of sectors. In addition, these structures frequently communicate and liaise with activists and organisations in communities elsewhere in the country. The activities of the Campaign include community organising, pickets and protests, public meetings, media campaigning, workshops, and solidarity and support of local struggles for access to information, freedom of expression, and the right to protest.

In March 2013 the delegates gathered at R2K’s third annual National Summit resolved to formally adopt a programme on “the right to protest”, thereby committing our structures to defending freedom of assembly and the right to campaign as crucial avenues for freedom of expression. These resolutions were strengthened and deepened at subsequent National Summits in 2014 and 2015.[1]

The necessity of expanding the work of the organisation in this way represents the growing concern within R2K structures and its member organisations that the right to protest is coming under increasing pressure, restriction and repression. While the urgency for this work had been highlighted by the horrific massacre of striking miners at Marikana in August 2012, it was also a response to the growing frustration and desperation of many civic structures across the country who find their right to protest being wilfully undermined by police, municipal authorities, and private companies, among other actors.

In light of this, this submission is limited to matters relating to the right to protest. Given the short time frames for comment on the paper, it has not been possible to consult widely within our provincial and local structures on the content of the Draft White Paper, so the comments in this submission draw on existing positions within the Campaign and the documented experiences of its members.

It is understood that White Papers are aspirational by nature, so this submission will not deal with the “reality gap” between the vision put forward in the Draft White Paper on policing and the current state of policing in South Africa. Rather, we will focus on specific problems with the vision put forward in the document, and some of the silences in the document which suggest a failure to confront some of the most significant problems regarding how current policing affects the right to protest.

We welcome the opportunity to respond to the Draft White Paper on Policing (and would like to acknowledge the decision by the Civilian Secretariat to extend the deadline for comments). However, from the outset we should note that the Draft White Paper scarcely mentions, let alone addresses, the most serious problems with policing of protests in South Africa today. If the right to protest is, to borrow from the Draft White Paper, “an essential element of life in a democratic space”, the outrageous daily infringements of that right by police need to be addressed urgently.

Section 2 will deal with the drift towards increasingly violent and intolerant responses to social protest. Section 3 will deal with growing concerns around intelligence-led methods in public order policing. Section 4 will deal with the need to confront the true roots of militarised forms of policing. Section 5 will conclude with specific recommendations.

2. Confronting violence in public order policing

2.1 Overview

Protest is the subject of daily public discussion in South Africa, whether in the media, in Parliament or from government podiums. Yet, as recent academic efforts have highlighted, these discussions are plagued by bad data and bad analysis[2], which appear to exaggerate both the scale of protests and their potential for violence. Police often argue that they are essentially under siege from rising protests and increasingly violent protesters[3] — what SAPS leaders called an “upsurge against state authority” when addressing Parliament on the matter.[4]

However, in order to properly understand this discussion, it’s important to cover what’s known about the scale and nature of protests in South Africa.

2.2 The scale of the protests in South Africa

Protest does appear to be on the rise in South Africa, though for a range of methodological reasons there are few statistics that quantify this increase reliably.

However, when it comes to the alleged surge in violence as a feature of protests, the police’s own data calls these claims into question.

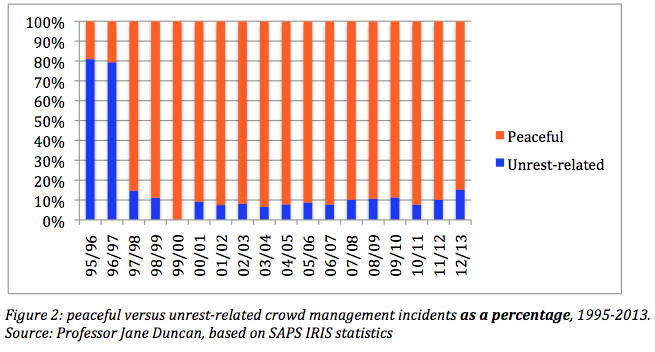

Figure 1: peaceful versus unrest-related crowd management incidents, 1995-2013. Source: Professor Jane Duncan, based on IRIS statistics

The police’s Incident Registration Information System (IRIS) does record a general increase in the number of “crowd-management incidents” since 1995, which includes both gatherings and protests. However, it also shows that the vast majority of these incidents are peaceful (figure 1), and that the rate of incidents recorded as “unrest-related” has increased only modestly as a percentage of the total (figure 2). This increase is especially modest considering that South Africa’ population increased by over 34% during that time – from 39 million people in 1995 to nearly 53 million in 2013.[5]

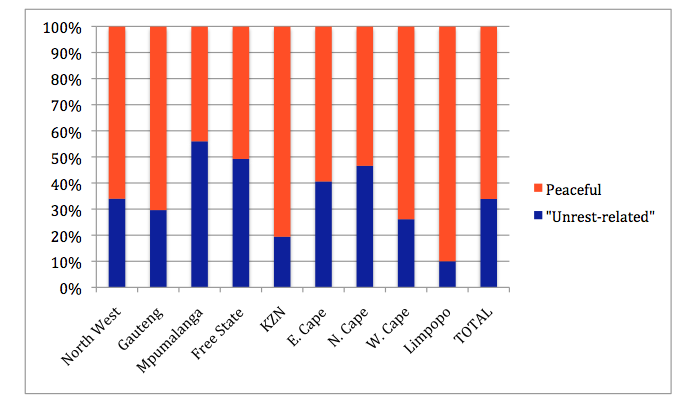

Looking closer at other available data from the IRIS database, counting only incidents tagged as “service delivery protests” between 2009 and 2012, show that on average 66% of recorded incidents were peaceful, versus “unrest-related”. (This data, released by SAPS under the Promotion of Access to Information Act, was disaggregated by province, not by year.)

Figure 3: peaceful versus unrest-related incidents tagged as “service delivery protests” as a percentage, 2009-2012. Source: Professor Jane Duncan, based on SAPS IRIS statistics

In light of these statistics, the primary emphasis on violence as a feature of protests appears to exaggerate the threat. An exaggerated understanding of violence as a feature in protests can do serious harm, if it fuels attitudes and policies that are less tolerant of dissent and freedom of assembly.

2.3 Concerning violence

It is also unhelpful to have a one-dimensional understanding of ‘violence’ as a phenomenon at protests. Firstly, this fails to appreciate the extent to which police conduct may instigate violence. R2K Campaign activists and member organisations have reported many instances where police have unilaterally and unlawfully ‘banned’ gatherings ‘on the spot’ and outside of the provisions of the Regulation of Gatherings Act. In these cases, protesters who have asserted their right to gather are often forcefully dispersed as police members violently enforce their unlawful decision. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that brutal and intolerant conduct from the police is often the first incidence of violence in a protest, and may instigate unrest on the part of protesters. (In this regard, police and other authorities who manipulate and bypass procedures in the Regulation of Gatherings Act in order to undermine or frustrate the right to protest are also a huge source and driver of conflict.)

In any case, when it comes to understanding incidents of unrest on the part of protesters, “violence” is an unhelpful catchall term. The University of Johannesburg’s South African Research Chair in Social Change has distinguished between peaceful, disruptive and violent protests; this they have done to make the point that while some protests may involve property destruction, they do not necessary involve violence where people are injured or even killed[6].

2.4 Quantifying police violence against protesters

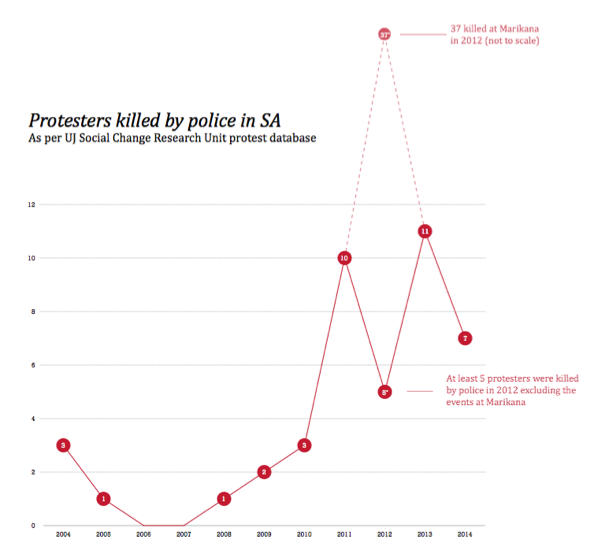

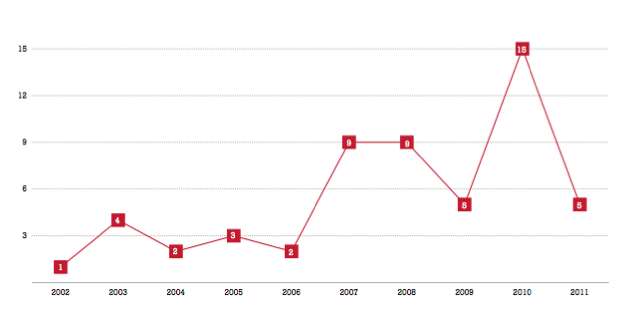

Figure 4: People killed by police during protests. Source: R2K Secret State of the Nation Report 2014, based on statistics by University of Johannesburg Social Change Research Unit

In contrast to the relatively modest increase of protests where incidents of violence or other disruptive acts are recorded, the available data shows a shocking increase in brutality on the part of police. This tallies with the lived experiences of civic activists who have long complained of violent police responses to legitimate protests.

Media monitoring by the University of Johannesburg Social Change Research Unit tracked a sharp upward trend in the numbers of people killed by police during protests between 2004 and 2014, even not counting the huge number of people killed by police at Marikana (Figure 4). At least some of those killed appeared to have been bystanders who were not involved in the protest at all.

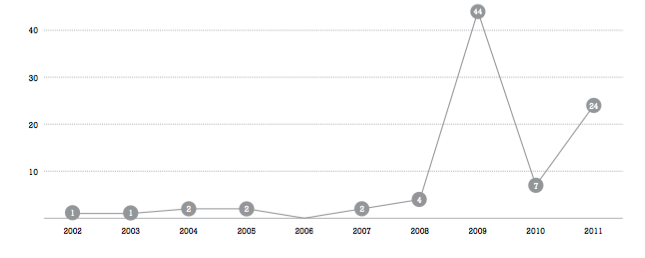

IPID does not regularly disclose statistics about its investigations of complaints related to public order policing, but a once-off disclosure of data on complaints of crowd control incidents shows the extent to which oversight structures have failed to check these abuses.[7] Complaints of police violence in crowd control incidents rose from five in 2006 to 16 in 2007, 25 in 2008 and 59 in 2009. Fifty-nine percent of the victims who laid complaints of police violence were involved in protest marches or demonstrations. This means that the rate of police violence has increased far more rapidly than the rate of unrest-related protests, which calls into question police claims that they were acting in self-defence. It should be noted that these statistics do not include the Marikana killings, as they were generated before the massacre.

Assault GBH was the most common complaint in crowd control: in fact, of the 204 cases reported to the ICD involving crowd control, 87 cases of assault GBH were reported (Figure 6). Cases in this category spiked in 2009, when members of the paramilitary unit, the Tactical Response Team (TRT), were accused of widespread assault in Mpumalanga. Of the 87 assault GHB cases reported over this period, 60 came from Mpumalanga alone.[8]

Figure 6: IPID cases of assault (GBH) in crowd-control situations. Source: R2K Secret State of the Nation Report 2014, based on IPID briefing to Parliament 30 August 2011

Figure 7: IPID cases of attempted murder in crowd-control situations. Source: R2K Secret State of the Nation Report 2014, based on IPID briefing to Parliament 30 August 2011

The police units that protesters complained about the most were station members, followed by the Public Order Police (POP). However, in relation to the complaints received from Mpumalanga, the National Intervention Unit and the TRT featured strongly in the complaints.

These crimes have largely gone unpunished. Of 204 complaints related to public-order policing between 2002-2011, only one resulted in a conviction, and two in acquittals after prosecution. Seventy-five cases were closed as ‘Unsubstantiated’ because a perpetrator could not be identified.[9] IPID has also acknowledged that it is extremely difficult to investigate cases of police violence in crowd control. Police members are generally not easily identifiable, as they do not have labels on their uniforms allowing them to be identified with certainty.

This problem led most famously to the acquittal of several police officers accused of Andries Tatane’s killing, but is clearly a more general problem – and surely contributes to a culture of impunity when it comes to unlawful conduct among police.

Unfortunately, the Draft White Paper does not adequately confront the absolute failure of existing oversight structures to deal with these abuses.

3. Confronting intelligence-led policing of protests

The Draft White Paper confirms the drift towards intelligence-led policing, while failing to acknowledge the downsides of this approach, particularly when it comes to the policing of protests.

The issue of police officers photographing or videotaping protesters is a frequent complaint among civic activists. In fact this is just the most visible manifestation of intelligence-led methods (as contained in National Instruction 4 of 2014) that create a range of problems.

3.2 National Instruction 4

In March 2014, SAPS National Commissioner Riah Phiyega signed off on National Instruction 4, which sets out the guidelines for intelligence gathering in public order policing. Like previous policies, it has a lot to say about how police must gather information on protesters. It lays out the following procedure:

- According to the policy, when the relevant officer receives notice that there will be a gathering, his or her first responsibility is to “make an attempt to gather information pertaining to the proposed gathering by using the POP [public-order policing] unit information network (and crime intelligence network where appropriate).” It does not state on what grounds it would be appropriate to involve Crime Intelligence.

- From there, the policy says that police must do a “threat assessment” (to anticipate possible unrest) – again, drawing on Crime Intelligence among other units. According to the policy, the threat assessment does not call for new information to be gathered, but should draw on “available operational information”, including “history of peaceful or violent protests by the parties involved [and] past experience with the parties”.

- Police must then assess the likelihood of violence, whether the participants will be aggravated or carrying weapons, and determine “the intention of the participants” and “any other information which is of importance for the operation.” It does not outline what methods should be used. The policy is silent on whether or not Crime Intelligence officials should participate in any pre-protest meetings between police and the protester organisers, although as we will see, this sometimes happens.

Other aspects of National Instruction 4 also have privacy implications:

- It states that POP units must have an Information manager “to take responsibility for the collection and supply of all information, before, during and after gathering to ensure informed tactical decision making in order to professionally police all gatherings.”

- Station commanders are given a vague mandate to use intelligence for pre-emptive policing, to “identify indicators of potential violent disorder in their areas by continuously gathering information…”

- According to the policy, “All potential or existing challenges and underlying factors must be analysed by intelligence and information structures…” – a very broad and vague mandate.

- The policy states that protests should be videotaped, and the footage stored for evaluation and training.

This policy does not give clear limitations on what methods should be used for this kind of information-gathering, or any requirement that the police should choose the least invasive means to carry out such assessment. There are no guidelines for how long information should be stored or when information should be discarded. Given the potential for these policies to infringe on a range of political rights, most especially the right to privacy, there are no provisions to ensure that the policies are “necessary and proportionate” to a legitimate aim, in keeping with international human rights law.[10]

These provisions also encourage a form of pre-policing, where people engaged in protest are profiled as potential criminals without any evidence of wrongdoing. Moreover, the existing policy, and the framework proposed by the Draft White Paper, fail to realise how uninvited surveillance from police can intimidate protesters exercising their lawful rights – thus infringing on the right to campaign.

3.3 The shift to intelligence-led policing in protests

These experiences are only likely to get worse. After a particularly disturbing spate of protester deaths in January and February 2014, the police announced a policy shift to ‘demilitarise’ public-order policing and adopt more “intelligence-led” methods.

This has been coupled with SAPS seeking to expand public order policing capacity on a massive scale, with a R3.3 billion plan that would nearly double public order policing personnel nationally, and drastically increase the SAPS arsenal of lethal and non-lethal weaponry. This has included a bid for more resources to gather intelligence for its public-order policing functions, including appointing more video operators and more ‘intelligence gatherers’, as well as extra funds for surveillance equipment such as long-range ‘listening’ devices.[11] (This submission deals with concepts of demilitarisation below.)

These policies have been adopted without public debate or buy-in, and no clear limits on what ‘intelligence’ is being gathered and through what means.

Available evidence suggests that intelligence-led methods in public order policing have been implemented without the consent or knowledge of citizens involved in protest. The experience in R2K’s structures has been that this approach has led to Crime Intelligence officials contacting civic organisations to interview them on their activities, political orientation and trajectory. In some cases, civic activists have discovered that Crime Intelligence officials are contacting their associates to gather information without their consent, and there have even been instances where organisations have detected attempts to get information on their activities covertly. The potential for these kinds of activities to encroach on lawful activity, and intimidate activists who are perceived to be critical of power-holders (including the police) cannot be over-emphasised.

3.4 Anticipating criminal behaviour?

Another problem is that these approaches may encourage authorities to anticipate criminality among people who are actually exercising their basic rights. There is a risk that authorities may begin to profile and predict who is ‘likely’ to engage in criminal behaviour, even if they have not done anything that is against the law.

4. Confronting the genuine roots of militarised policing

The Draft White Paper reaffirms the NDP in committing the police to demilitarisation, yet understands it in the most superficial of senses as a cultural issue (the police thinking of themselves as a military by another name). This understanding fails to recognise the more substantial indicators of militarisation. A key criticism of the current efforts to demilitarise the police, as announced by Minister Nathi Nhleko in September 2014, is that they appear to focus only on superficial aspects of militarisation while ignoring some of the deeper aspects of a militarised system.[12]

The shallow conceptualisation of police militarisation in South Africa is discussed in Professor Jane Duncan’s recent book, The Rise of the Securocrats: The Case of South Africa (2014, Jacana Publishing).In that text, Duncan draws on one of the foremost academics on police militarisation, Peter Kraska, who has defined police militarisation as the implementation of an ideology that stresses the use of force and threats of violence to solve problems, and uses military power as a problem-solving tool.[13] In other words, as a problem that manifests in material, cultural, organisation, and operational ways.

Kraska explains that all police forces are militarised to some extent. However, the extent of militarisation can be measured on a continuum of indicators ranging from material indicators (the extent of martial weaponry), cultural indicators (the extent of martial language), organisational indicators (the extent of martial arrangements) and operational indicators (the extent of operational patterns modelled after the military).[14]

Some of the indicators of this militarisation include the increasing use of the military in internal security matters, the growth in the establishment and deployment of elite police units that are modelled after military special operations units and that are paramilitary in nature, and the application of military models to domestic policing functions. Many of these indicators are evident in South Africa, particularly when examining how protest is policed.

4.2 Ending the use of paramilitary units in public order policing

In South Africa, as elsewhere, this has led to the establishment of paramilitary policing units, trained in military techniques that are mandated to adopt a ‘zero tolerance’ approach to fighting crime, even if it means using maximum and even lethal force in what are considered high-risk policing operations. However, in reality these units have not been confined to high-risk operations; they have been employed in a range of civil policing functions, including public order policing. This leads to a gradual normalisation of paramilitary teams in policing more generally. As discussed above, the use of paramilitary units in policing protests in South Africa has led to an outrageous number of cases of brutality against protesters, illustrating that where military ideology becomes normalised, the use of unnecessary force becomes normalised too.

4.3 Intelligence-led approaches as a militarised tactic

As discussed above, the increased emphasis on intelligence-led methods in public-order policing has been introduced as part-and-parcel of demilitarisation. However, this is not satisfactory. As shown, there is great potential for surveillance methods to be extremely intrusive and disruptive.

Surveillance may be less violent than other methods, such as use of rubber bullets and tear gas, but can be extremely intrusive. If combined with political interference – as many civic activists complain they have experienced – intelligence-led methods may just lead to more targeted forms of violence, whereby authorities are able to identify leaders of protests – “troublemakers” in order to target and harass them.

Other ‘non-violent’ resources that have been championed as part of this demilitarised approach include ‘non-lethal’ crowd-control measures such as long range acoustic devices (commonly known as ‘sound cannons’).[15] These emit sounds that are painful to the human ear, and can even cause deafness. Because the devices target people indiscriminately, they can also affect people in the vicinity of a protest, and not just the protesters.

5. Recommendations

This submissions ends with the following recommendations:

5.1 Bring an end to police violence against protesters

Any roadmap to a safer and more just democratic society must include a programme to end the extraordinarily brutal and aggressive forms of policing which characterise too many interactions between citizens and the state. The Draft White Paper needs a much keener awareness of the extent to which police brutality is a defining feature of much protest in South Africa. To the extent that policy discussions of protest appear to exaggerate and mischaracterise the role of ‘violence’ on behalf of protesters, this Draft White Paper also appears to fall into the trap of failing to recognise the frequent role of police brutality in creating conflict and increasing the risk of unrest during protests. As a minimum step it should require an immediate end to the use of paramilitary units in crowd-control situations of any kind.

5.2 Strengthen legal protection for protesters

Civic organisations engaged in protests often report instances where police and other authorities have manipulated or deviated from the Regulations of Gatherings Act, by putting unlawful and arbitrary restrictions on the right to gather, or unilaterally and unlawfully ‘banning’ gatherings. This effectively criminalises people for exercising the right to protest, and creates a pretext for police to arrest or use violence against protesters who assert their right to gather. This has been identified as a major driver for conflict in protest situations. The Regulation of Gatherings Act needs to be strengthened to ensure protesters’ rights are properly protected against such conduct.

5.3 Develop a path to genuine demilitarisation of policing

We welcome a commitment to demilitarise policing in South Africa, but as noted above, this will not yield results if it is based on a superficial understanding of militarisation. The Civilian Secretariat should develop a framework to monitor indicators of police militarisation, including periodic audits of indicators such as the use of militarised weaponry, training, and operational norms.

5.4 Curtail intelligence-led methods in public-order policing

The Draft White Paper mirrors current policing policy, in as much as it fails to appreciate the enormous potential for intelligence-led methods in public-order policing to lead to infringements of privacy, intimidation, and inappropriate invasive policing of civilians who are, ultimately, exercising basic rights. As a minimum, any framework for intelligence-led policing of protests should be brought in line with the principles of international human rights law which require that potentially intrusive acts must be “necessary” and “proportionate” for the pursuance of a legitimate aim.[16]

5.5 Address the failures of the oversight structures to bring perpetrators of police brutality to justice

The admission that IPID has secured only one conviction out of 204 complaints against police conduct in protests is an indictment. It goes without saying that unless the system identifies and punished perpetrators of police brutality, the offences will continue while public cynicism deepens.

#Ends

References:

[1] See R2K National Summit reports at www.r2k.org.za/documents

[2]J Duncan, “The Politics of Counting Protests”, Mail&Guardian 16 April 2014

[3] See for example Remarks by the Minister of Police at the SAPS Public Order Policing Conference, 31 January 2014

[4] Business Day, “Funds Needed to Control Protests, 8 September 2014

[5] World Bank, World Development Indicators databank, available at data.worldbank.org

[6]C Runciman. ‘A protest event analysis of community protests 2004-2013’, South African Research Chair in Social Change, University of Johannesburg’, 12 February 2014.

[7]Independent Police Investigations Directorate, ‘Briefing on crowd control’, presentation to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Police, 30 August 2011

[8]Ibid, pg. 11

[9]Ibid, pg. 18

[10] See the ‘Necessary and Proportionate’ Principles at https://necessaryandproportionate.org

[11]Rebecca Davis, “Public Order Policing: SAPS demands more muscle,” Daily Maverick, 3 September 2014

[12]See Jane Duncan, “The lang-arm of the law is a deadly dance.” Mail & Guardian 8 August 2014

[13]Kraska, ‘Militarisation and policing’, p. 503, cited in J Duncan, Rise of the Securocrats: the Case of South Africa, Jacana Publishing, 2014

[14]Ibid., p. 504.

[15]SAPS presentation to Parliament, 3 September 2014

[16] See the ‘Necessary and Proportionate’ Principles at https://necessaryandproportionate.org