Analysis: Signs of a deep rot in state-security structures

A long-awaited report reveals SA spooks’ endless battles with funds, efficacy and independence

The joint standing committee on intelligence (JSCI) broke its three – year long silence last Thursday by finally tabling its much-awaited annual reports for 2010 and 2011-2012. (See the report here.)

The reports detail internal turmoil within South Africa’s spy agencies, missed targets, wasteful expenditure and a worryingly sharp increase in the use of its surveillance capabilities.

The JSCI, a parliamentary body made up of about 13 parliamentarians from across the party political spectrum, is designed to provide civilian oversight of the intelligence services.

The committee’s independence has always been vulnerable to executive capture, the most recent example being its sweetheart Nkandla report which backed the “security-related” expenditure and absolved President Jacob Zuma of any wrongdoing.

One of its main duties is to table a report before Parliament by March 31 each year detailing the previous year’s activities. These reports are the public’s only window into the activities of the country’s spy agencies. Since 2009, however, no reports had been tabled.

Why the delay?

In the 2011-2012 report, reasons given for the delay include a failure by the crime intelligence division of the police to deliver its reports timeously, the lack of “synchronicity” between reporting periods specified in other legislation and the Intelligence Services Oversight Act, as well as “sensitive” reasons that cannot be disclosed. None of these explain the three-year delay in releasing the reports.

The JSCI reportedly attributed the delay to the fact that the reports were awaiting approval by the president to ensure they did not compromise national security.

The 2011-2012 report also notes that “the 2010-2011 report was only forwarded to the president in October 2013”.

The inclusion of the president in the tabling process is inexplicable. Neither the oversight Act nor parliamentary rules require it; at best, the Act provides for the JSCI to provide a copy to the president and the relevant ministers after the report is tabled in Parliament.

The apparent decision to offer a preview of the report to the president therefore raises significant questions. It is not impossible to surmise that the damning picture painted by the reports of the disarray in the crime intelligence division, particularly its beleaguered former boss Richard Mdluli, may have provided some grist to the presidential filibuster mill.

Instability in crime intelligence

This instability, extensively chronicled in the media, includes the appointment of four divisional commissioners between 2011 and 2013, the cloud of allegations surrounding Mdluli and the fraud and corruption charges brought against head of covert support services, General Solomon Lazarus.

The JSCI details its numerous efforts to arrest the deepening malaise in crime intelligence. It lists the instances when meetings were held, inquiries and task teams established and reports prepared. Yet, in almost all instances, the efforts were futile.

The report describes the committee as “unable to get the necessary co-operation from crime intelligence”. It further describes “infighting and lack of trust” in crime intelligence as having thwarted its efforts.

Financial turmoil

The auditor general’s reports included in the JSCI reports further indicate an agency mired in wasteful, irregular or unaccountable expenditure. The State Security Agency, the umbrella intelligence body established through the General Intelligence Laws Amendment Act, irregularly spent over R86-million in 2011-2012, earning a “qualified” audit from the auditor general.

Adequate documents were not provided, over 40% of planned “targets” were not achieved and supply chain management regulations were not followed. Goods and services were not competitively bid for.

The annual budget allocated to state security – now amounting to over R4-billion – was never tabled before the JSCI, thus preventing any civilian oversight regarding how taxpayer money is spent.

It is in the crime intelligence division that wasteful expenditure has reached its lowest nadir. Glaring irregularities include the observations that the division ‘understated’ over R47-m of irregularly spent funds. No audit evidence was provided to support over R278-million in various transactions listed.

The auditor general further noted that no document management system exists and the auditor general was thus unable to verify the proper financial status of the crime intelligence division.

Interceptions

The JSCI’s much-delayed reports also contain yearly briefings from the so-called “Rica judge”, which provide the public’s only glimpse into the state’s official use of communications surveillance between 2009 and 2011 – although it is much like peeking through a narrow keyhole into a cluttered, dust-filled room.

The reports by Judge Joshua Khumalo, the “designated judge” who authorises state security bodies to conduct lawful surveillance in terms of the Regulation of Interception of Communications Act (Rica), give more information than was available under his predecessor, but are nonetheless alarming both for what they show, and also for what they may obscure.

Dramatic increase

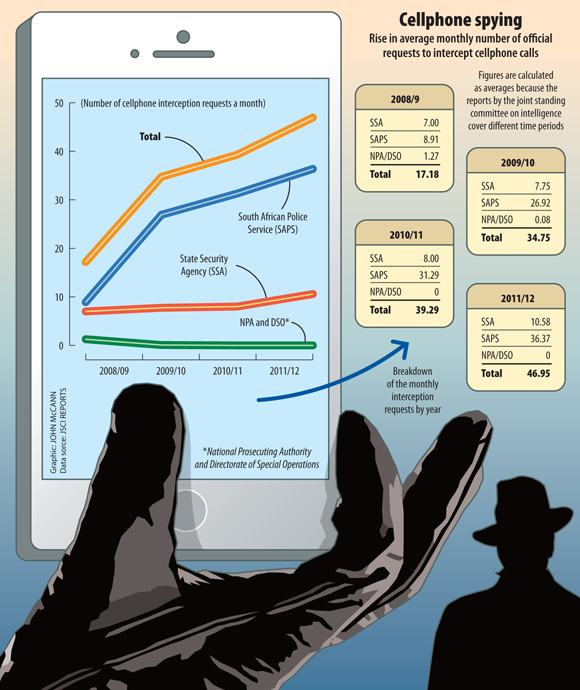

The reports show a dramatic rise in the use of formal communications surveillance through Rica from 2008 to 2011. The bulk of this appears to be under crime intelligence, which was making an average of nine Rica requests a month in 2008, but nearly 40 a month by the end of 2011.

In total, Khumalo reported that by the end of 2011 there was a monthly average of about 47 requests a month from all divisions (crime intelligence, the domestic and foreign agencies under state security and military intelligence).

Potential abuse of emergency clause

The Khumalo briefing also stated that in one year the South African Police Service invoked emergency regulations 3 217 times to trace people’s locations using their cellphones.

These were “section 8” requests – a “life and limb” provision for security bodies to get a user’s location from their network provider. Because it is designed for emergencies, the network provider and law enforcement are only required to give supporting documents to the Rica judge after the fact.

Khumalo notes that, in the most recent year under review, MTN had not provided any supporting documents for section 8 requests.

If this resulted in any penalties, it has not come to light. Khumalo does note that Parliament should consider amendments to the Act “to prevent any possible abuses by state agencies and service providers”.

Crime intelligence’s appetite

Why crime intelligence should have increased its use of surveillance so dramatically is open to speculation. Khumalo’s briefing suggests that it “may be due to a realisation by the law enforcement agencies of the effectiveness of interceptions”.

Yet the spike in interceptions occurred at a time when the JSCI concedes there were “serious problems” at crime intelligence that made it “predictable that the performance of the division would be negatively affected”.

In other words, at a time when crime intelligence’s investigative capacity was at least partly compromised, it was bugging more phones than ever before.

Amid concerns that the state may be abusing its surveillance powers, fuelled by media reports of people in state-security bodies manipulating the Rica process or bypassing it completely to monitor people’s communications, the incomplete picture given here is only likely to fuel paranoia.

Khumalo was at pains, in briefing the JSCI in 2011, to note that he had found no evidence of this kind of abuse.

But at least one such abuse has come to light since then: in 2011 it emerged that the Sunday Times journalist Mzilikazi wa Afrika had been bugged under Rica under Khumalo’s watch.

How the JSCI and the Rica judge have addressed this matter, as with many things, we will have to wait for the next JSCI annual report.

This points to a bigger problem: essentially, the Rica judge and the JSCI give so little usable information on surveillance that it is not entirely clear that they serve a public oversight role at all.

In 2013, Jane Duncan, an academic at Rhodes University, made detailed requests to the department of justice to access information on the effectiveness of Rica – including the cost per interception and, most importantly, the number of arrests and convictions that stem from interceptions. The department rebuffed the request, saying that the information she was requesting “was supplied in strict confidence by various third parties”.

The paltry data on Rica intercepts provide only a few insights on the use (and potential misuse) of surveillance.

If there is one insight to be gleaned, then, it is this: at a time when there needs to be a broad and substantive debate about the role of state-security bodies and the use and regulation of surveillance technology, citizens are groping around in the dark. The debate is starved of basic, vital information.

A version of this article, by Vinayak Bhardwaj and Murray Hunter, appeared in the Mail&Guardian.