R2K’s Secret State of the Nation report – with infographics

Introduction: Addressing SA’s climate of secrecy

The R2K Secret State of the Nation report shows that 2013 will be a critical year for the right to know, with signs of increasing secrecy in our politics and daily lives – and plenty of opportunities to tackle it

In yesterday’s State of the Nation Address, the President made few commitments towards improving openness, access to information, or freedom of expression – with the welcome exception of pledging to achieve 100% public access to broadband in South Africa by 2020.

However, the broader climate of secrecy and a growing culture of securitisation remains unchallenged in his roadmap for the nation. His address only once mentions the Bill of Rights – and this was to assure South Africans that violent protests would be more aggressively policed. Leaving aside the growing concerns that aggressive and militarised policing has itself led to tragic and outrageous abuses of protestors’ rights, the President failed to acknowledge that many of the laws governing the right to assembly in South Africa – including the Regulations of Gatherings Act and National Key Point Acts – often do more to restrict this right than to enable it.

The Right2Know Campaign’s 2013 Secret State of the Nation Report shines a light on the existing climate of secrecy in South Africa, and the need to tackle ugly practice of individuals and elements in the State security sector and private corporations who favour secrecy as a means to ensure that they enjoy a greater hold on power.

Secrecy robs us all equally of the opportunity for real social justice. Some secrets might be necessary – the criminal justice system and the state-security cluster do indeed keep secrets that save lives. However, far too much information is withheld from public view by individuals who, with increased frequency, fail to live up to the values enshrined in our Constitution.

In this report we highlight three upwards trends in secrecy:

- The use of the apartheid-era national security law, the National Key Points Act, has risen by more than 50% over the past five years. The secrets hidden in the expenditure on the President’s private homestead in Nkandla may be indicative of a much wider abuse of national-security secrecy.

- Secret political party funding from private donors has boomed in the past decade and is likely to double in the period 1998-2014. It buys influence for the powerful in selected corporations, foreign governments and shadowy organised crime, and is a legalised form of bribery favoured by almost all political parties.

- The over-classifying of government documents since 1996 will come to a head this year with the passing of the Secrecy Bill. A huge body of secret documents (all classified under the 1996 Minimum Information Security Standards, which has no legal standing) will come under extraordinary new protection this year, despite containing a mix of genuine national-security documents with the minutes of board meetings, financial disclosure forms, and salary reports. An analysis of all available data on the extent of documents classified in a single year shows that vast numbers of documents have been classified without proper oversight or restriction, and in defiance of the public’s right to know.

Finally, early this year the President is likely to be presented the Protection of State Information Bill (the Secrecy Bill) for signature. Few laws have so focused the public mind on the problem of secrecy in our society and the increasing power and influence of the country’s securocrats in our politics and daily lives.

Should he choose to exercise his powers to refer the Bill to the Constitutional Court, the President would affirm to the nation his commitment to building a progressive society characterised by openness, and to tackling the creeping culture of secrecy currently facing South Africa.

Should he choose to pass this Bill into law, however, he will strengthen the growing public resolve to stop the unjustifiable secrecy, to stop the grab for power by securocrats and their cronies, to stop the lies.

– The Right2Know Campaign

Section 1: Ordinary people, ordinary secrets

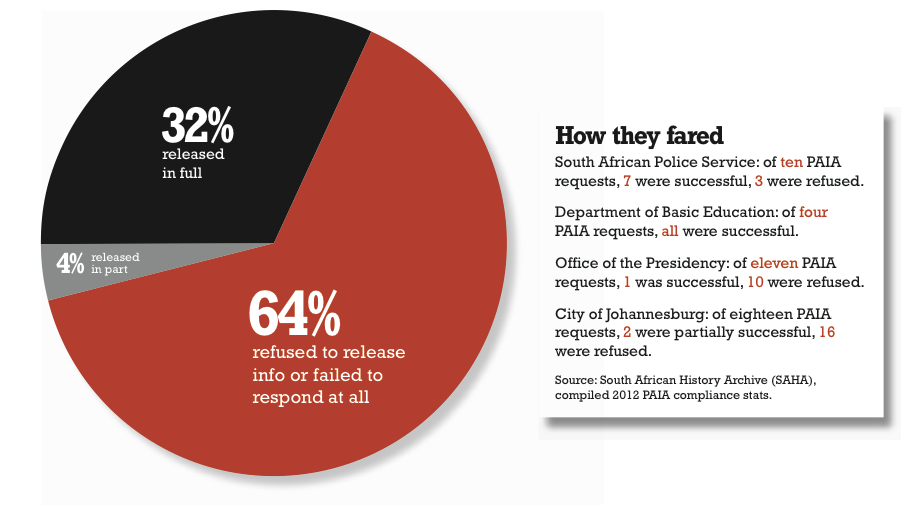

South Africa’s access-to-information provisions appear to be failing, as 2 out of 3 formal requests for information are refused

The Problem: If compliance with the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) is a litmus test for the state of government and corporate accountability, the signs are worrying.

In 2012, the South African History Archive (SAHA) surveyed all the PAIA requests that they had administered in the past year: of 159 requests for information held by various public and private bodies, 102 were either outright refused or simply received no answer (which is a deemed refusal under the law) – or 64 percent. This suggests a genuine crisis in the mechanisms that are meant to ensure the public’s right to know.

As a mark of the long and costly process of forcing better compliance with the provisions of PAIA, on the same day as the State of the Nation Address last week, the Mail&Guardian finally won a court battle to access a report to then-President Mbeki on the 2002 Zimbabwean elections – four years after their PAIA application was refused.

However, 2013 will see the passing of an amendment to PAIA gives new recourse to people seeking access, in the form of an Information Commissioner that will have legal powers to force bodies to comply with PAIA requests. But this is not enough, if the underlying problem is a lack of commitment to openness on the side of information holders.

Information should be released proactively, in an open and accessible form, and PAIA should only be a last resort. While the ‘big ticket’ secrets get much attention, many South African are denied much more basic information that they need in their daily lives and struggles. From data related to housing lists, to the water licenses of all mining operations, many civic organisations and community groups are seeking information that should already be available online and in every municipal office.

How to fix it:

* Government and the private sector must commit to proactive release of open data, and ensure all officials comply with the letter and spirit of access-to-information laws.

* Find out more at www.r2k.org.za/info-access-now and see the Open Data & Democracy Initiative.

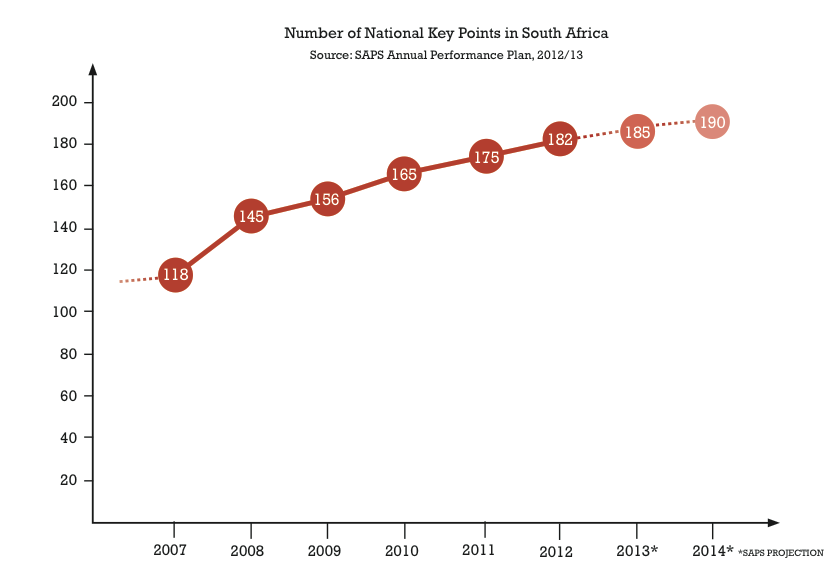

Section 2: The number of secret ‘National Key Points’ is rising

In the last 5 years, there’s been a 54% increase in the number of ‘national key points’ across the country – but we still don’t have a list of them.

Problem: The National Key Points Act empowers the Minister of Police (or anyone to whom he delegates the power) to declare any building a ‘national key point’ – a place that is so important to national security that it needs extra security, extra protection, and extra secrecy. The National Key Points Act restricts access to certain kinds of information about these places, and prohibits people’s right to assemble or protest there.

Although it’s an apartheid-era national security law, R2K has drawn together data that suggests it is still being used widely today – the number of national key points has grown by more than 54% in the past 5 years.

Any site can be named a key point, from our airports and factories to our power stations and presidential residences – yet the public doesn’t even know which buildings now fall under the Act. This means that you could be breaking the law without even knowing it, by staging a protest at a national key point or even photographing it.

R2K has called for SAPS to make the list of national key points public, using the Promotion of Access to Information Act. SAPS initially refused this application, but we have appealed, and a response is due at the end of February.

How to fix it:

* SAPS must release the list of South Africa’s national key points

* Parliament must take steps to repeal the National Key Points Act

* Find out more at www.r2k.org.za/national-key-points

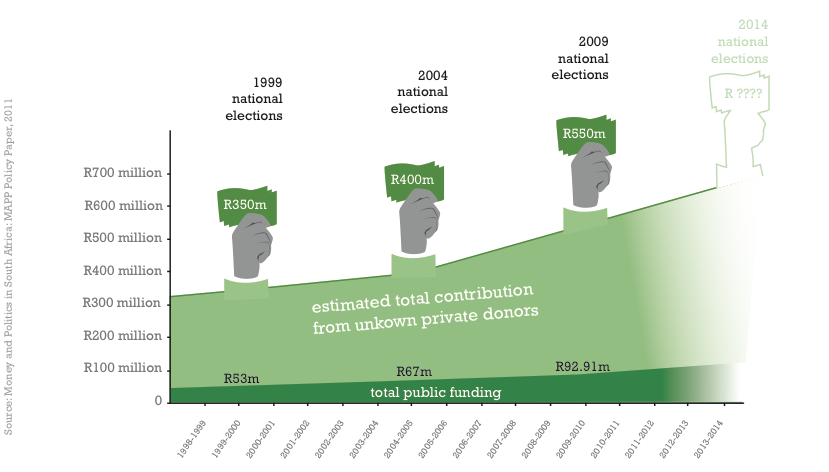

Section 3: Secret party funding set to increase

As South Africa heads for its most expensive elections ever, citizens still don’t know who is bankrolling our country’s political parties.

The problem: The funding by private donors of South African political parties is a secret which all major political parties refuse to disclose. It subverts the will of the people and buys influence for powerful corporations, foreign governments and shady organised crime figures. Influence has the potential to buy tenders, subvert justice, and shift public policy from a path that favours the poor, to one that benefits the rich and well-connected.

The status quo allows parties to establish private companies that benefit from state contracts – pushing up costs and potentially lowering services. It is the poor who pay.

The amount of money raised by parties for elections now runs into hundreds of millions of rand, and is set to rise further – meaning more secrets, scandals and lies. These stretch from funding allegedly received by the ANC from the murderous kleptocrat Mohammed Suharto in the 1990s to the DA’s recent ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ scandal involving the Guptas.

We welcome the ANC’s Mangaung resolutions to create legislation to regulate party funding, and the DA’s somewhat reluctant commitment to do the same. However, political parties are quick to talk and slow to act when it comes to the secrets of mega-funding.

As we approach the 2014 national elections, and funding is set to continue sky-rocketing, it is time to shine a light on the secrets which empower the rich and politically connected at the expense of everyone else.

How to fix it:

* Parliament must pass a comprehensive law requiring parties to disclose their private funding before the 2014 elections!

* The law must be based on broad public engagement and cannot become a new set of bad rules brokered by party hacks in closed rooms.

* Find out more at www.osf.org.za/programmes/money-and-politics-project and www.myvotecounts.org.za.

Section 4: Secrecy Bill set to pass into law with worst provisions intact

Despite a number of progressive changes, the Protection of State Information Bill still contains broad and harsh penalties that could be used to target whistleblowers

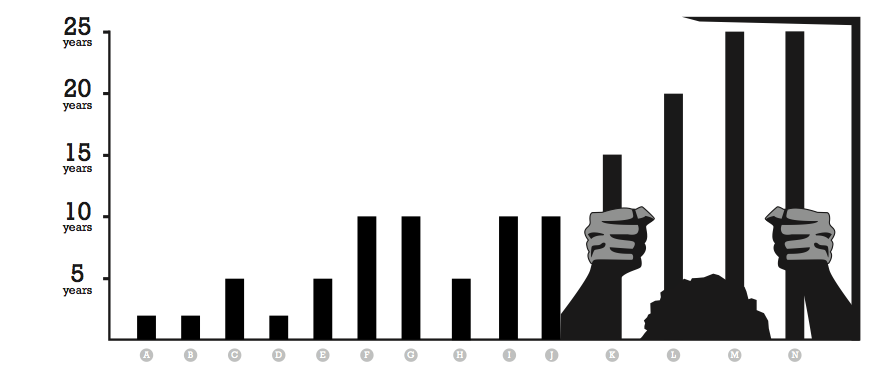

Offences & Penalties in the Secrecy Bill:

A) 2 years – Failing to comply with the provisions of the Act if you are an official or the head of an organ of state.

B) 2 years – Intentionally destroying, removing, altering or erasing “valuable information”.

C) 5 years – Intentionally providing false information to a national intelligence structure.

D) 2 years – Gaining unauthorised access to any computer which belongs to the State.

E) 5 years – Modifying the contents of any computer which belongs to the State with the intention of impairing the operation of any computer, programme or data.

F) 10 years – Modifying or destroying classified information or otherwise rendering it ineffective.

G) 10 years – Producing, selling, designing, distributing or possessing any device which is designed to overcome security measures for the protection of state information, OR using such a device to overcome security measures designed to protect state information.

H) 5 years – Disclosing or possessing classified state information. Limited public interest defence.

I) 10 years – Intentionally intercepting any (electronically communicated) classified information without authority. No public interest defence.

J) 10 years – Harbouring or concealing a person who you know, or have reasonable grounds to believe or suspect, has committed or is about to commit an offence classified as espionage or hostile activities. No public interest defence.

K) 15 years – Classifying state information for ulterior motives, including to conceal corruption, incompetence, inefficiency or administrative error, or to prevent embarrassment. No public interest defence.

L) 20 years – ‘Hostile activities’: Communicating classified state information which you know would directly or indirectly benefit a non-state actor engaged in hostile activity that would prejudice the national security of the Republic. No public interest defence.

M) 25 years – ‘Espionage’: Communicating classified state information which you know, or ought reasonably to have known, would directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state. No public interest defence.

N) 25 years – ‘Espionage’: Receiving classified state information which you know would directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state to the detriment of the national security of the Republic. No public interest defence.

The problem: As the newly amended Secrecy Bill heads for its final hurdle in the National Assembly, its provisions would criminalise the public for possessing information that has already been leaked, and place severe restrictions on civil servants, journalists and members of the public seeking to expose unjust secrets. Though a limited public interest defence has been introduced in one provision, prosecutors can easily bypass it by charging you under different provisions of the Bill.

It now seems inevitable that the National Assembly will rubberstamp this Bill and pass it to the President to be signed into law.

How to fix it:

* Parliament must produce a truly just classification law which promotes openness over secrecy and meets the 7-Point Freedom Test, failing which the President must refer it to the Constitutional Court

* Find out more at www.r2k.org.za/secrecy-bill

Section 5: Secrecy Bill will protect vast body of existing secrets – even unjust ones

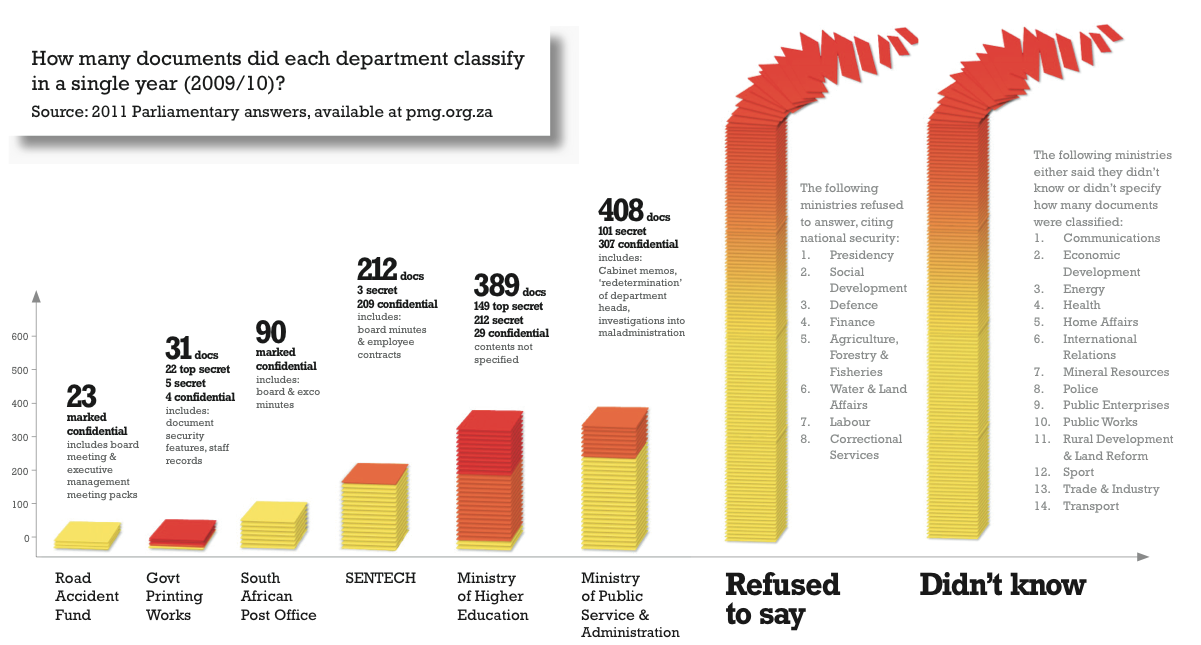

Yellow = Confidential | Orange = Secret | Red = Top Secret

The problem: Since 1996, the making and keeping of government secrets has been guided by a policy called the Minimum Information Security Standards, which has no legal standing.

In 2011, the Parliamentary opposition wrote to all government departments asking how many documents were classified the previous year. Some of the most prominent government departments (including Presidency, Defence, Finance and Water & Land Affairs) refused to answer for national security reasons, saying the number of secret documents was itself a secret. The majority of the remaining bodies said they simply did not know how many documents they had classified.

However, the few detailed responses provided by the remaining departments and agencies were indicative of serious inconsistencies in policy. Some documents clearly fell under genuine security concerns – such as the Government Printing Works’ documents which detail the security features that are built into passports, or documents revealing the identities of whistleblowers in internal corruption investigations managed by the Public Service Commission.

However, other documents’ security relevance is questionable at best, including the minutes of board meetings, and 7,584 financial disclosures forms being held by the Public Service Commission. And the justification of 389 documents classified by the Ministry of Higher Education remains unknown. (However, it must be noted that those departments that provided detailed, if in some cases shocking answers are probably better practitioners of openness than those departments who could not or would not say how many secrets they harboured.)

When the Protection of State Information Bill becomes law, this vast body of existing secrets will have extraordinary new protection, since the Bill is designed to retroactively protect all information classified by pre- and post-1994 policies. In other words, the Bill will protect previously classified information, even if the classification was unjustified or wouldn’t have been allowed in terms the new Bill itself. In terms of clause 55(2), the Protection of State Information provides that all these documents should be reviewed by a special panel, but does not provide any timeframe.

How to fix it:

* The Protection of State Information Bill must meet the R2K 7 Point Freedom Test.

#ENDS

Download the report here, share it with others, and tweet us your thoughts @r2kcampaign or let us hear from you on our Facebook page.